Author Archives: Admin

Libération

Le Temps

Le Parisien Weekend

L’Express

Le Point

Naples: Elena Ferrante’s brilliant city – The Guardian

Fans of the writer’s Neapolitan novels are flocking to discover the south Italian city, whose personality is as important to the books as the protagonists

Lisa O’Kelly

Sun 25 Feb 2018 07.00 GMT

Like many tourists in Naples, I have only ever been there en route to somewhere else. For years the city has had a reputation for being dirty, dangerous and traffic-choked: why on earth would anyone choose to linger? But this has changed. Naples is becoming a destination in its own right, thanks in part to the huge popularity of the enigmatic author Elena Ferrante. And with the city’s rubbish-collection problem solved and new traffic restrictions in the centre, it is looking in better shape than it has done for decades.

Ferrante, who writes under a pseudonym, is the most important literary sensation to have emerged from Italy in a generation. Her quartet of Neapolitan Novels has sold more than 5.5 million copies worldwide. The New York Times observed that enthusiasm for the novels is so intense that it is being described in “epidemiological terms, making the phenomenon sound almost like an infectious disease”. Nor is Ferrante fever likely to cool any time soon: an Italian/American television adaptation of the first book My Brilliant Friend is under way. Filming starts in Naples next spring. The ultimate aim is to adapt all four novels over 32 episodes.

I came late to the books, prompted to pick up the first volume by the outrage around Italian reporter Claudio Gatti’s controversial unmasking of Ferrante’s supposed true identity. Needless to say, I loved My Brilliant Friend and devoured the next three, gripped by Ferrante’s rich portrait of the hard lives and intense friendship of the two protagonists – Elena and Raffaella (who call each other Lenù and Lila) – who grow up in a poor, violent neighbourhood against a background of mafia vendettas and social and political unrest in the 1960s and 70s.

We stop at a traditional pastry shop like the one run by the Solara brothers for a coffee and a sfogliatella

Naples is as much a character in Ferrante’s writing as Lenù and Lila themselves. Her “dark streets full of dangers, unregulated traffic, broken pavements, giant puddles … clogged sewers” work their way deep into your imagination. So you finish the Neapolitan novels not only with a sigh of regret, but an insistent desire to get to know the city for yourself.

“People began asking hotels and tour operators in the area: ‘How can we find the locations in the novels?’” says Caterina dei Vivo of Progetto Museo, a Naples-based cultural heritage preservation group. “They wanted to see the stradone, the Vomero, the Rettifilo, the Corso Umberto.” Progetto Museo quickly launched a Ferrante tour of the city earlier this year and several others have jumped on board since then.

I decided to combine my tour with a few nights in Sorrento. A picturesque tumble of dark red villas and ochre hotels perched on the edge of the Bay of Naples, the town works as a base not only for visits to the city – about 50 minutes away by boat, or an hour by train – but for the Amalfi coastal path (the “pathway of the gods”), Campania’s hillside towns and the islands of Capri and Ischia, too. Pompeii and Heculaneum are an easy train ride away.

I was met off the boat from Sorrento by the impressively qualified Caterina, a Neapolitan with a PhD in the preservation of cultural heritage. Along with the two others in our group, I was keen to visit the working-class neighbourhood where Lenù and Lila grow up: the Rione Luzzatti in the south of the city. Frustratingly, Caterina won’t take us there. Now mainly social housing, it has a reputation for crime and is apparently “too sad and depressing” for us. Instead, we set off into the old city where our first stop was Corso Umberto, known locally as the Rettifilo. This is the main street connecting the rione [administrative district] with the city, where Lenù and Lila first start going out alone with friends – with disastrous consequences one night when the Solara brothers pick a vicious fight with some obnoxious private school boys. It is also home to the bridal shops visited by 16-year-old Lila as she prepared for her lavish wedding to Stefano Carracci. Every window is awash with frothy white lace and rainbow-coloured bridesmaids’ dresses.

Three sheets to the wind … a backstreet in Spaccanapoli. Photograph: Alamy

We turn left into the university district where Lenù found her first job in a bookshop and Nino, the love of her life, worked as a leftwing lecturer. As in the books, the lecture theatres are daubed with radical slogans – a “lotta dura” [a 60s political slogan, now more associated with football] here, a hammer and sickle there and students hand out revolutionary flyers to passersby. Next stop is Via dei Tribunale, where Lenù attended political meetings with her friends in the Red Brigades. We stop at a traditional pastry shop like the one run by the Solara brothers in the novels for a coffee and a sfogliatella, a shell-shaped pastry which originated in Naples, filled with vanilla, cinnamon and orange-flavoured ricotta.

The city centre feels wonderfully unmodernised, its dark, narrow streets dripping with faded laundry, lucky bunches of dried red chillies outside every house and shop front. Walls are buried beneath layers of posters, stickers, graffiti and grime. Scooters zoom past, horns blare and truck brakes hiss. I’m struck by the absence of chains, such as Starbucks and McDonald’s. Caterina says the multinationals know they cannot compete with the street food of Naples: fried pizza, potato croquettes, courgette flowers in batter, fried anchovies and fried mozzarella are sold on every corner in brown paper cones – cuoppo – for just a few euros apiece. Pungent Neapolitan coffee likewise.

Ferrante Scores in Germany, France – Publishers Weekly

By Jim Milliot | Feb 23, 2018

Elena Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child landed in the top spot in France at the end of January and was in second place on Germany’s bestseller list last month. The novel was published in the U.S. in fall 2015 by Europa Editions.

At the end of last month, Still Me by JoJo Moyes was in first place in Germany; the novel has been at the top of PW’s charts as well since its release in early January. Bernhard Schlink’s newest novel, Olga, was in third place on the bestseller list. Schlink had a huge hit in the U.S. in 1995 with The Reader, and his most recent book released in America was The Woman on the Stairs, which Pantheon published last March.

Back in France, two new books followed Lost Child on the fiction list. In second place was Prix Goncourt–winner Pierre Lemaitre with his latest, The Colors of Fire. In the third spot was And Me, I Still Live by Jean d’ Ormesson, the highly respected French novelist of more than 40 books and member of the Académie Française, who died in December.

Two nonfiction titles led the combined bestseller list in the Netherlands in January: Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury and A Retrospective of 2017 by Han van Bree. Dan Brown’s Origin was in fifth place. (Origin was also #2 in Spain, #3 in Sweden in fiction, and #4 on Italy’s combined list.)

Love Letters to Authors – Elena Ferrante – Tattered Cover

Dear Elena,

Many love you because you’re unavailable. Despite international acclaim, you have firmly chosen to remain out of the public eye, concealing your true identity and writing under a pseudonym. You choose this in part because, as you’ve said, “Books, once they are written, have no need of their authors.” How can we not be intrigued and seduced by you?

Your Neapolitan novels focus on the lives of two girls, Lenu, our narrator, and her brilliant friend, Lila. Both grow up poor in Naples, Italy during the aftermath of WWII. The books follow the pair’s divergent paths to adulthood; one becomes upwardly mobile through education and the other struggles for autonomy and a better life in their poor neighborhood. The book is just as much about the shifting political, economic, and cultural forces at play in Italy during this period. These potentially intimidating themes are brought back to earth by delivering them through the lives and experiences of the two extraordinary characters and their evolving relationship.

Your work is enormous in its scope and deeply layered, while still managing to be relatable. The Neapolitan Novels are about the nuances of friendship and intimacy between women as much as they’re about the epic struggle for autonomy and agency in a deeply unequal and shifting society. You have written a book that is unsentimental yet has a great, bursting heart, a series that explores the light and dark of friendship and the machinations of power. You capture the intense interior experiences of living in a society that works to confine you, and you also beautifully articulate the divine rage and rebellion which seethes within those subject to these oppressive experiences. You have written a ‘serious’ piece of literature with cover art that is unapologetically feminine.

Elena Ferrante, I love you because your work is transcendent. You defy definition and you irreverently rebel against attempts to categorize your writing. You gave me a new understanding of what art can be.

— Colleen

Top 10 books about cheating – The Guardian

From illicit James Salter to category-defying Jeanette Winterson, here are the best contemporary works about romantic infidelity

Why do we keep coming back to the adultery novel? What is it about infidelity that bears retelling across the centuries, especially now, when the ancient prohibitions against sex outside marriage have all but disappeared? These are questions I asked myself as I was writing Fire Sermon, the story of a married woman’s physical, intellectual and spiritual affair with a married poet.

I’m not sure I have all the answers. However, given the current cultural moment, I believe it’s a crucial time for female artists to write frankly and openly about female sexuality in all its forms: longing, shame, guilt, transgression, ecstasy. The assumption that male writers can have sexually transgressive imaginations while female novelists should be more demure is passé. If we’re going to secure gender equality, we must be allowed the same imaginative expression, on the page, as our male counterparts.

Further, women are bravely speaking out against male abuses of power and sexual coercion in the workplace – but what about sexual coercion and abuse within a marriage? Or within the context of religion, where traditional gender roles and prohibitions against extramarital sex might make it difficult to speak up? Perhaps my protagonist Maggie’s predicament – to stay or not to stay in the marriage – will serve as a platform for discussion.

When I initially drafted this list, I began with the obvious suspects: Anna Karenina, Lady With the Pet Dog, Madame Bovary and The End of the Affair. But these works are always included on lists like this. With these classics taken as read, I’ve listed only contemporary works, all published in my lifetime. I’ve also included a poetry collection and a short story, because I think the compression of these forms is suited to the intensity of the subject matter.

4. The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante (2002)

I read this on vacation one summer, in a single sitting, paralysed with the exquisite literary sickness that comes from the combination of aesthetic appreciation on the one hand, and recognition of oneself on the other. An account of a woman’s mental unravelling after her husband leaves her for a much younger woman, the book’s power is in its fearless, closeup details (I can’t think of a more painful animal death scene) and in the ways the narrative subtly implicates the reader: given a certain set of horrific circumstances, I, too, might be capable of this psychic fury.

School Library Journal

Guest Post: A New Consideration of Elena Ferrante’s The Beach at Night by Dr. Ellen Handler Spitz

You guys know my penchant for children’s books that fall outside the usual norms. And nothing strikes fear in the good American heart faster than picture books from other countries. I’ve seen even the most sophisticated of readers wrinkle their noses at translations they deemed “weird”. And nothing caused such wrinkling better than the 2016 publication of the American edition of Elena Ferrante’s picture book The Beach at Night. Kirkus argued that the book was not, “a true picture book: with many text-only double-page spreads and illustrations that do little to extend the text, this book will try the patience of most young listeners. The Italian edition of this book is marketed to children 10 and up; the advertised audience in the United States of 6 to 10 feels just plain wrong.” The New York Times was hardly any more kind. And yet, it has its defenders.

Today, guest poster Dr. Ellen Handler Spitz, author of such books as The Brightening Glance: Imagination and Childhood and many others, comments on the book and its reception. Take it away, Ellen!

Mysterious, hugely popular Italian novelist Elena Ferrante wrote a children’s book, The Beach at Night, that has curried scant favor in the American press since its 2016 translation by Ann Goldstein. I would like to advocate, albeit gently, for this book. A doll named Celina, left behind on a beach at the end of one day by five-year-old Mati, tells us how that feels: the story is told in her voice, that of an anthropomorphic toy.

Mysterious, hugely popular Italian novelist Elena Ferrante wrote a children’s book, The Beach at Night, that has curried scant favor in the American press since its 2016 translation by Ann Goldstein. I would like to advocate, albeit gently, for this book. A doll named Celina, left behind on a beach at the end of one day by five-year-old Mati, tells us how that feels: the story is told in her voice, that of an anthropomorphic toy.

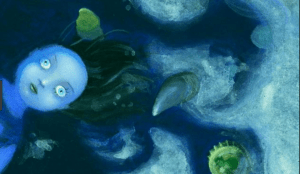

Ferrante’s theme— abandonment —touches children’s deepest fears. It plays out within the intimate, oft blurry bonds between a little girl, her doll, and her mother. With short, direct sentences, Ferrante unfurls a catalogue of woe. Being neglected comes first, as Celina watches Mati go to play with Minù, the new kitten her visiting father has just brought her. Humiliation arrives next. Rejected and cast off on the beach, Celina suffers maltreatment by Mati’s grumpy brother, who dumps burning sand on her. Physical discomfort follows fast, and then terror, as the family leaves the beach without her, and the sky changes color. A “Mean Beach Attendant” with a huge Rake frightens her and flings her onto a pile of trash. Fear morphs into sadness and anger. Anxious about being hurt and broken, Celina remembers Mati’s former love. Envy comes barreling in, as she pictures the kitten Minù who has supplanted her and wants spitefully to spoil him. Vindictively, she conjures him having bouts of diarrhea and imagines vomiting on him so that Mati will be compelled to forsake him: an apt projection on Ferrante’s part, since little girls, when expected by their mothers to be clean, may feel unlovable when not.

Loneliness and boredom ensue. Followed by confusion. The Mean Attendant ignites a fire to burn residual beach trash, including Celina. She uncomprehendingly welcomes its warmth because the sunless beach has grown cold. Gradually, however, she understands that the fire which pleases her can destroy her. When it scalds her dress, she chides (as to a naughty pet): “Bad fire.”

Ferrante is partaking, of course, in a time-honored tradition in which dolls come to life in children’s books. Two long-lived examples might be cited: Rachel Field’s Newbery Award-winning Hitty of 1929, in which a doll carved from magical wood recounts her hundred year journey, and the ever-beloved Raggedy Ann stories of c. 1900, in which a stuffed rag doll with a candy heart from grandma’s attic has nocturnal escapades that author Johnny Gruelle based on observations of his daughter Marcella. Turning to animation, there’s Pixar’s Toy Story of 1995, by John Lasseter. Ferrante mines this vein in several novels, including The Lost Daughter and My Beautiful Friend, where dolls play quasi-human roles. Her pages, however, often portray toy characters in nightmarish settings fraught with anxiety.

The Beach at Night, moreover, employs language unpurged of slang (for which, however, as New York Times reviewer Maria Russo points out, the translator may be held responsible), and, as I have emphasized in Inside Picture Books, a reading adult is always free to substitute one word for another. The term “caca,” translated here with an expletive, might easily be rendered by the childish expression “doo-doo.” Nevertheless, Ferrante’s book has been judged by some to be inappropriate for children. Respectfully, I demur.

Many books for young children tend to be protective; only rare ones plumb the intensity of feeling to which small children are prey. Maurice Sendak’s oeuvre, of course, stands as an exception. As does Ferrante’s The Beach at Night. Like Jezibaba or Medea, Ferrante dips into the cauldron without gloves, seizes fears, yanks them out, and thrusts them under the glaring strobe lights of her prose. In so doing, she performs a service not unlike that of Sendak, who, in his masterpiece Where the Wild Things Are, unfastens a door and shoves us in, or, better yet, pushes us in and closes the door fast behind us.

Many books for young children tend to be protective; only rare ones plumb the intensity of feeling to which small children are prey. Maurice Sendak’s oeuvre, of course, stands as an exception. As does Ferrante’s The Beach at Night. Like Jezibaba or Medea, Ferrante dips into the cauldron without gloves, seizes fears, yanks them out, and thrusts them under the glaring strobe lights of her prose. In so doing, she performs a service not unlike that of Sendak, who, in his masterpiece Where the Wild Things Are, unfastens a door and shoves us in, or, better yet, pushes us in and closes the door fast behind us.

Perhaps you are wondering: But, why explore pain in a children’s book? My best reply would entail a wondrously wise 1959 text called The Magic Years by Selma Fraiberg, distinguished University of Michigan psychologist. This classic exploration of young children’s inner lives unsurpassed for more than a half-century tells a cautionary tale about Frankie, a little boy whose devoted parents are eager to do him right. They consult experts, identify typical childhood fears, then systematically keep those fears at bay. Nursery rhymes are edited; fairy tales purged of witches and ogres. When a pet parakeet dies during Frankie’s nap, it is replaced before he can notice. His baby sister’s birth is planned to minimize feelings of jealousy, rivalry, and displacement. Yet, Frankie suffers all the ordinary fears of early childhood and bad dreams as well. Endemic to human growth, Fraiberg explains, fears emanate largely from within. Since they cannot be expunged, growing children need to learn to invent solutions, as Fraiberg puts it, “to the ogre problem.” Ferrante’s Mean Beach Attendant, for example, replete with lizard-like moustaches and nasty ditties seems merely an update of the ogre or bogeyman, familiar from European folk tales.

Elena Ferrante gets this. Her fierce grasp of its truth informs her slender book. No emotion in The Beach at Night is foreign to young children because, as we have come to recognize, at least since the late 19th century, even the youngest have active inner lives despite their lack of words with which to report on it. Fear, envy, confusion, longing, disappointment, anger, and sadness are all poignantly felt. That said, where better to practice coping than in the pages of a story book? Children who encounter danger in books, especially with adults present to help interpret, can do so safely. If intense emotional exploration serves a boon in art and literature for grown-ups, why should it not be made available for children? The Beach at Night offers vicarious adventures that, for some children, may provide a proving ground for mastery, while for others, undeniably, its scenes will be too scary. Parent-and-child or teacher- or librarian-and-child may collaborate to make that call, and this in itself can constitute valuable learning.

Abandonment tops the list of childhood terrors. A college student of mine surprised me in class when she nailed the most abject horror of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl. Not darkness, she whispered. Not freezing cold. Not starvation. But the fact that the little girl cannot go home. Cast out, she dies on an empty city street.

Ferrante plots Celina’s abandonment with exquisite care. Good turns suddenly to evil and then occasionally reverses. Mati’s love for her doll Celina morphs into rejection. The hot beach becomes chilly at night. The comforting fire harms what it warms. A sea wave saves Celina from fire but then engulfs and nearly drowns her. The aptly colored black and white kitten starts as a rival for Mati’s affection but ends up being the creature who improbably saves her, brings her home, and becomes, at the book’s end, her friend. Mati’s father, kindly giver of the kitten, serves as a foil for the other adult male character, the Mean Beach Attendant, who calls Celina “ugly” and nearly annihilates her.

Ferrante plots Celina’s abandonment with exquisite care. Good turns suddenly to evil and then occasionally reverses. Mati’s love for her doll Celina morphs into rejection. The hot beach becomes chilly at night. The comforting fire harms what it warms. A sea wave saves Celina from fire but then engulfs and nearly drowns her. The aptly colored black and white kitten starts as a rival for Mati’s affection but ends up being the creature who improbably saves her, brings her home, and becomes, at the book’s end, her friend. Mati’s father, kindly giver of the kitten, serves as a foil for the other adult male character, the Mean Beach Attendant, who calls Celina “ugly” and nearly annihilates her.

All these turnabouts match young children’s mental lives, where perceptions reverse in a flash. The hand that caresses stiffens into a spank. The angry grimace softens to a twinkle. Lacking analytical ability as yet and information with which to explain these turnabouts, children find their unpredictability both magical and terrifying.

Darkness matters. Night is when mysterious events take place. And Ferrante uses the beach elsewhere in her work, especially in The Lost Daughter, where her protagonist “rescues” a doll forgotten on a beach and then holds on to it, unable to bring herself to return it to the child who longs for it. As in The Beach at Night, which it eerily overlaps, The Lost Daughter blurs boundaries between girl and doll, mother and daughter, boundaries breeched again by Ferrante in the opening pages of another novel My Brilliant Friend, were two girls play in tandem with their dolls, conversing with them and imitating each other like miniature characters in a Pirandello play until the one with the ugly doll throws another’s beautiful toy into a dark cellar.

A paradigmatic moment in The Lost Daughter occurs when the narrator, mother of two faraway grown daughters, anxiously watches a young mother on the beach with her little girl and a doll. Eavesdropping, she hears the names of mother, daughter, and doll all seem to mingle and merge: Nina, Ninù, Niné, Nani, Nena, Nennella, Elena, Leni. Switching back and forth from childish to grown-up voices as they play, this mother and daughter make the mute doll “speak” as if it were both mother and child without separation. Envious of their fluidity and yearning for lost moments in her own life, the narrator finds the scene intolerable. Unhinged, she rises to intervene, willing them to stop.

That Lost Daughter scene illuminates a key moment of recognition in The Beach at Night. The beach has turned dark; no stars or moon appear, and the abandoned doll Celina recalls her little mistress Mati saying to her in her mother’s voice, “If you catch cold, you’ll get a fever.” Suddenly, the doll understands: Mati is repeating her own mother’s words “because Mati and I are also,” as Ferrante writes, “mother and daughter.” The next thought is surely what Aristotle would have called a peripeteia. Celina comprehends that, because of this identification, Mati cannot possibly have forgotten her. She is not abandoned! And children encountering the story understand. On the last page but one, Mati, having Celina back, hugs her with a face wet with tears.

What then is Celina, the doll? The renowned British pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald W. Winnicott coined the term “transitional object.” He meant by this a blanket, stuffed animal, or dolly that is neither exclusively the child’s “me” (self) or “not-me” (other) but a quirky amalgam that gets created in the context of the closest human relationship and used to play it out. Ferrante shows us this small miracle and never lets up. Right there on the sand, each of us is led through the dread of abandonment. But, as we close the book with our children, we may feel more aware of and grateful for the loved ones who abide with us, both child and adult.

Le Journal du Dimanche

The Guardian

Author of bestselling Neapolitan novels says she was keen to test herself with the ‘bold, anxious exercise’ of writing regular pieces for the magazine

Elena Ferrante, the bestselling Italian novelist of the highly acclaimed Neapolitan series, is to write her first ever regular newspaper column, in the Guardian.

The pseudonymous author’s return to writing, a year after an investigative journalist controversially claimed to have revealed her real identity, will be welcomed by fans anxious to see her next move. Ferrante has always said that her anonymity was important to her work, freeing her from the “anxiety of notoriety”.

Now, in her weekly column for the Guardian’s Weekend magazine, Ferrante will share her thoughts on a wide range of topics, including childhood, ageing, gender and, in her debut article, first love. Ferrante said she was “attracted to the possibility of testing myself” with a regular column, and called the experience “a bold, anxious exercise in writing”. The column will be translated by Ferrante’s regular collaborator Ann Goldstein.

“I’m thrilled to be working with Elena Ferrante on her first newspaper column – a new adventure for her and for Guardian Weekend magazine,” said editor Melissa Denes. “Every week, she will be writing a personal piece, covering subjects from sex to ageing to the things that make her laugh. We can’t wait to see where she will take us.”

Ferrante’s books, particularly her Neapolitan series, have been bestsellers among English readers since the first volume, My Brilliant Friend, was translated in 2012. Narrated by a woman called Elena – or Lenu – the series follows her life and that of her friend Lila as they rebel against the poor and stultifying Naples neighbourhood they grew up in. The three novels that followed – The Story of a New Name (2013), Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2014), and The Story of the Lost Child (2015) – have all made bestseller charts around the world. Frantumaglia, a collection of the author’s essays and letters, was released in 2016.

She is also currently working on the screenplay for a television adaptation of My Brilliant Friend for HBO.

Ferrante was named one of the world’s most influential people in 2016 by Time magazine, and was one of the highest-earning literary novelists in the UK in 2017, despite not releasing a new book that year.

The Guardian’s Weekend magazine has been redesigned as part of the newspaper’s move to tabloid format, with the first new-look issue appearing on 20 January.

L’Obs

Elena Ferrante, grand entretien exclusif : “L’histoire de Lila et Lena est terminée”

Par Didier Jacob

Publié le 17 janvier 2018 à 17h02

Il aura fallu un seul livre pour qu’une romancière italienne, encore inconnue il y a sept ans, devienne l’une des personnalités les plus en vue de ce début de siècle. Un phénomène d’autant plus inouï s’agissant de l’auteur d’une fresque à l’ambition littéraire indéniable (et non d’un roman pour jeunes adultes comme naguère la série des «Harry Potter»), fresque dont les références nombreuses à l’histoire italienne et à l’ancrage géographique, limité pour partie à un quartier de Naples, semblaient condamner à l’avance tout succès à l’exportation. (…)

Derrière son masque, Elena Ferrante distille ses interventions avec une parcimonie d’apothicaire. Les entretiens qu’elle a donnés se comptent sur les doigts d’une seule main, entretiens qu’elle n’accepte de donner que par mail, son éditeur italien jouant les boîtes aux lettres. Son désir d’anonymat n’est, on l’a compris, pas négociable: pour elle, le livre une fois terminé doit se défendre seul. Brisant le silence qu’elle s’impose presque toujours, elle explique ici comment elle a conçu, dans le plus grand secret, «l’Amie prodigieuse».

Les Echos