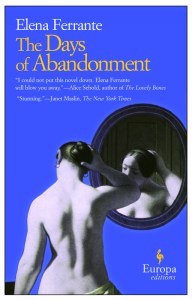

Translated by Ann Goldstein

2005, pp. 192, Paperback

$ 15.00 / £ 7.99

ISBN: 9781609452766

—The New York Times

Read reviews

Read it now:

Read reviews

From illicit James Salter to category-defying Jeanette Winterson, here are the best contemporary works about romantic infidelity

Why do we keep coming back to the adultery novel? What is it about infidelity that bears retelling across the centuries, especially now, when the ancient prohibitions against sex outside marriage have all but disappeared? These are questions I asked myself as I was writing Fire Sermon, the story of a married woman’s physical, intellectual and spiritual affair with a married poet.

I’m not sure I have all the answers. However, given the current cultural moment, I believe it’s a crucial time for female artists to write frankly and openly about female sexuality in all its forms: longing, shame, guilt, transgression, ecstasy. The assumption that male writers can have sexually transgressive imaginations while female novelists should be more demure is passé. If we’re going to secure gender equality, we must be allowed the same imaginative expression, on the page, as our male counterparts.

Further, women are bravely speaking out against male abuses of power and sexual coercion in the workplace – but what about sexual coercion and abuse within a marriage? Or within the context of religion, where traditional gender roles and prohibitions against extramarital sex might make it difficult to speak up? Perhaps my protagonist Maggie’s predicament – to stay or not to stay in the marriage – will serve as a platform for discussion.

When I initially drafted this list, I began with the obvious suspects: Anna Karenina, Lady With the Pet Dog, Madame Bovary and The End of the Affair. But these works are always included on lists like this. With these classics taken as read, I’ve listed only contemporary works, all published in my lifetime. I’ve also included a poetry collection and a short story, because I think the compression of these forms is suited to the intensity of the subject matter.

4. The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante (2002)

I read this on vacation one summer, in a single sitting, paralysed with the exquisite literary sickness that comes from the combination of aesthetic appreciation on the one hand, and recognition of oneself on the other. An account of a woman’s mental unravelling after her husband leaves her for a much younger woman, the book’s power is in its fearless, closeup details (I can’t think of a more painful animal death scene) and in the ways the narrative subtly implicates the reader: given a certain set of horrific circumstances, I, too, might be capable of this psychic fury.

The Vacation Book List You Never Knew You Needed

4. Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante

As you might know, Elena Ferrante is a pseudonym and there has been widespread speculation over who Ferrante really is, although she is widely believed to have been unmasked by the New York Review of Books in 2016, a move which was heavily criticised by Ferrante’s readers as unnecessary and an invasion of her privacy.

Days of Abandonment, published in Italian in 2002, predates her more famous books, the Neapolitan Novels. However, for me, it was the book that woke me up to her writing and led me to notice Italian writing.

In Days of Abandonment, Mario tells his wife Olga that he is leaving her. She soon finds out that he is living with his new girlfriend, a much younger woman. The book describes the days that follow Mario’s departure. It starts with Olga’s inability to comprehend that her husband, the father of her children, has ceased to love her.

Through the course of the book, Ferrante brilliantly portrays the frantic churning of an ‘abandoned’ woman’s mind. In fact, I found her writing so furious and unsettling that 50 pages or so in, I had to put the book away for a few days to see if I still wanted to read it. I did pick it up again.

This is not a long book, so it is a good one for a flight or to read in a day or two. (188 pp. Europa Editions)

100 MUST-READ INDIE PRESS BOOKS

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante, Ann Goldstein (Translator) (Europa Editions): A national bestseller for almost an entire year, The Days of Abandonment shocked and captivated its Italian public when first published. It is the gripping story of a woman’s descent into devastating emptiness after being abandoned by her husband with two young children to care for. When she finds herself literally trapped within the four walls of their high-rise apartment, she is forced to confront her ghosts, the potential loss of her own identity, and the possibility that life may never return to normal.

August 10, 2017

(…) Ferrante’s The Days of Abandonment, translated by Ann Goldstein, was so good it ruined me for other books for a long time. Darker and tighter than the sprawling My Brilliant Friend, it drills into the psyche of Olga, a woman spiraling out of control after her husband leaves her and their two young children. In one scene, Olga tells her daughter to poke her in the thigh with a knife to keep her from being distracted. Ants infest the apartment, the dog dies from insecticide, the hot summer days give everything a sheen of violence. A lot happens in a short space. But there’s more to women in translation than Ferrante, no?

The Days of Abandonment – Elena Ferrante (2002) (Transl. Ann Goldstein)

About a year ago, after seeing Suicide Squad, my longest-time friend started talking about this Italian author who wrote under a pseudonym, raving in particular about her novel concerning a woman being left by her husband. I forgot the name of the writer–but there were enough details to remember (female, Italian, pseudonym) that I could piece together who she was.

I finally got around to picking up The Days of Abandonment in late June, and took it with me on a recent trip to New York. Just as we were landing in New York, my seat neighbor inquired if the book was good, and I recited the above regarding the recommendation. He told me he had read My Brilliant Friend and the other trilogy. I told him I was surprised it was published in 2002, but that I hadn’t heard of it until now. He said he thought it was because Hollywood had come knocking.

The Days of Abandonment is a first-person narrative from the perspective of Olga, a 38-year-old mother of two (Gianni and Illaria), recently left by her husband, Mario. To get more detailed, Mario leaves her for a younger woman, the identity of whom is unexpected, and sort of obvious at the same time. Olga basically falls apart, and the novel is about her going crazy. It culminates in a sort of nightmare day from the hell, after which she gains some form of clarity on her situation.

Ultimately, it is a very satisfying novel, and sprinkled with that sort of European attention to detail and simplicity of style that feels effortless. The opening line is a perfect example, immediately reminiscent of another European master (Camus):

“One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me.” (9)

Okay, that is not nearly as simple as the opening of The Stranger, but that same sense of the immediate impact of sorrow is struck. The novel takes the shape of 47 relatively short chapters of varying length, which feel more like sketches of scenes. It seems to take place over the course of six months, but the primary action in the novel is the day that comes right around month four (Saturday, August 4th), chapter 18 – 34, pp. 88-151. A great deal of this section has to do with the locks on the front door. She manages to lock herself and her family inside of their apartment because she cannot undo the locks. She has a special set installed, with two keyholes that have to be turned just right. As a person that has had to call a locksmith to get into his apartment after his key broke off in the door, at least once, maybe twice, I could identify highly with this section. However, it goes a little bit too far! Here is one example I randomly flipped to:

“But I knew immediately, even before trying, that the door wouldn’t open. And when I held the key and tried to turn it, the thing that I had predicted a minute before happened. The key wouldn’t turn.

I was gripped by anxiety, precisely the wrong reaction. I applied more pressure, chaotically. I tried to turn the key first to the left, then to the right. No luck. Then I tried to take it out of the lock, but it wouldn’t come out, it remained in the keyhole as if metal had fused to metal. I beat my fists against the panels, I pushed with my shoulder, I tried the key again, suddenly my body woke up, I was consumed by desperation. When I stopped, I discovered that I was covered with sweat. My nightgown was stuck to me, but my teeth were chattering. I felt cold, in spite of the heat of the day.” (117)

She has a new set of locks installed after a set of earrings from Mario’s grandmother go missing. She has a vaguely unpleasant, vaguely sexual experience with the two men installing the locks, particularly the older of the two. The book is filled with such vignettes. Her complicated feelings about herself as a sexual being culminate in an encounter which ends up becoming an unlikely, ambivalent romance.

Her relationship with the family dog, Otto, is also worth comment. Otto is arguably a bigger character than either of the children, because she feels more saddled with him than the children. It seems as if Mario was the one to get him, but does not take him with him, and she resents the additional responsibility. But as always tends to happen, she develops a bond with the animal–however, not before a somewhat shocking incident in the park following another woman’s reproach after he scares her and her baby:

“When he didn’t stop I raised the branch that I had in my hand menacingly, but even then he wouldn’t be silent. This enraged me, and I hit him hard. I heard the whistling in the air and saw his look of astonishment when the blow struck his ear. Stupid dog, stupid dog, whom Mario had given as a puppy to Gianni and Ilaria, who had grown up in our house, had become an affectionate creature–but really he was a gift from my husband to himself, who had dreamed of a dog like that since he was a child, not something wished for by Gianni and Ilaria, spoiled dog, dog that always got its own way. Now I was shouting at him, beast, bad dog, and I heard myself clearly, I was lashing and lashing and lashing, as he huddled, yelping, his body hugging the ground, ears low, sad and motionless under that incomprehensible hail of blows.

‘What are you doing?’ the woman murmured.

When I didn’t answer but continued to hit Otto, she hurried away, pushing the carriage with one hand, frightened now not by the dog but by me.” (54)

There could be many more things to say about this novel, but I don’t believe in spoiling several of the smaller details. For example I found this feature in the New Yorker by James Wood which covers much of the same ground of this review, but divulges a few more details. It is also probably much better written because it was composed and edited as part of a day job, rather than a hobby masquerading as an entryway into the limited commercial landscape of art. Suffice to say, sometimes spoilers are necessary to explain my estimation of a novel’s worth, but I think the halfway point of a story is (generally) a fair boundary. It spoils nothing to say however, that anybody who has ever been dumped or left to their own devices–especially those left in Olga’s unfortunate position–will find some measure of solace in this work. Regardless of one’s perspective, there is great humanity and truth within it, and a likely catharsis for the reader.

BookREVIEW: Days of Abandonment

Reviewer Lynda Woodroffe

Mother and housewife Olga, 38, is left by her husband Mario, 40, for a girl they have both known since she was fifteen. Olga and Mario have two children and a dog, and live in a flat in a tower block in Turin. This is a story of a midlife crisis; of Mario who questions his male power, and Olga, whose fantasy life gets popped like a balloon.

Throughout her marriage Olga spent most of her time pleasing her husband, feeding his every whim to ensure that he remained hers. Like every woman who believed the myth of the princess who wins her prince, Olga became the housewife who lived her life through her husband and children – an unlived life, a life without appreciation and gratitude, a life of unmet needs, and neglect for personal development and talent: ‘I had put aside my own aspirations to go along with his. At every crisis of despair I had set aside my own crises to comfort him … I had taken care of the house, I had taken care of the meals, I had taken care of the children, I had taken care of all the boring details of everyday life…’ (p63).

But when Mario saw Carla, someone younger and fresher, he wanted her, so he went for her and won her. And this is where the story starts, with the opening line of the book reading: ‘One April afternoon… my husband announced that he wanted to leave me…’

The trauma at being abandoned and becoming a single parent led to many negative reactions for Olga. She neglected her children, forgot to feed them, did not notice when her son was ill, and leant heavily on her daughter for support. In the following weeks she nosedived from a lack of focus to complete breakdown, through an agonizing loss of her sense of self and her short-term memory. She embarked on a fantasy world, unable to conceive of the mess her now empty life had become, rearing up like a void before her. She neurotically scrubbed the flat clean before letting out the dog, who needed walking. When it returned it was ill and eventually died, probably from ingesting rat poison. In her self-deprecation, she believed she killed the dog and, perhaps, poisoned her own son: ‘Give back to me a sense of proportion. What was I? A woman worn out by four months of tension and grief; not, surely, a witch who, out of desperation, secretes a poison that can give a fever to her male child, kill a domestic animal….’ (p118).

Meanwhile, in the fog of her unreality, Olga self-harmed to stay present:

‘“Why did you put that clip on your arm?” asked her daughter Ilaria. … The tiny pain it caused me had become a constitutional part of my flesh…

“It helps me remember. Today is a day when everything is slipping my mind, I don’t know what to do.”

“I’ll help you.”

“Really?” I got up, took from the desk a metal paper cutter. “Hold this…. If you see me getting distracted, poke me…. Prick me until I feel it”.’ (p133)

In an attempt to relieve the pain, to create a distraction and to tell herself that she was still attractive, Olga seduced an undesirable neighbour, Carrano, a man who could play romantic music, but who could not make love. This led to self-disgust and frustration with whom she had become. She questioned her own identity and blamed herself for the loss of her marriage, asking herself obsessively what had happened in those ten years of matrimony: ‘For Mario I – I shuddered – had never been Olga. The meanings, the meaning of her life – I suddenly understood – were only a dazzlement of late adolescence, my illusion of stability.’ (p124)

Later, in discussion about custody of the children, her husband told her that she had to have the children more often because ‘…. You’re their mother’. (p185) Is he not their father?

Ferrante does not hold back on her characterization of abandonment. It is detailed and upsetting to say the least. Olga is so isolated and lost and this, I feel, is surprisingly universal. Ferrante describes what all women may feel following such an abandonment: that their lives will never be the same again.

While Olga’s life indeed never will be the same again, her mid-life crisis may be the end of the first part of her life and a time for change and, perhaps, betterment. Carl Jung believed that this time of life was a normal part of adult maturation, an opportunity for change. Jung (1971) identified five stages of life resulting in individuation, which arrived between the ages of 38 and 44 and which he called a creative illness. This crisis was the primary task of the second half of life.

The late adolescence that Ferrante’s Olga mentioned in this book (p124) is also synonymous with the Intimacy v. Isolation conflict listed in Erik Erikson’s psychosocial theory about the development of the personality (1950, p.255), whereby ‘.. the young adult, emerging from the search for and the insistence on identity, is eager and willing to fuse his identity with that of others … the avoidance of such experiences because of a fear of ego-loss may lead to a deep sense of isolation and consequent self-absorption’.

Erikson’s stages suggest that Olga’s regret at the loss of this seemingly ecstatic time can transform into another stage, the midlife crisis, which occurs during the 35-64 years and is a time for questioning the meaning and purpose of one’s life.

This devastating but short story gives us a cameo of a woman in the throes of change through loss, disbelief, to mistrust, and, hopefully, of a woman who will learn through her dismal experience and become fulfilled by her later discoveries. Elena Ferrante, author of seven other books about Italian women (particularly of Neapolitan women) and their lives and relationships, does not fail in her accurate sketches, which will resonate with all women across the world.

Lynda Woodroffe is a psychotherapist based in North West London and a member of the Contemporary Psychotherapyeditorial board.

Elena Ferrante: The Mad Adventures of Serious Ladies

by GD Dess

JULY 29, 2017

WRITERS FROM Charlotte Brontë, Virginia Woolf, Jane Bowles, and Mary McCarthy to Emma Cline, Ottessa Moshfegh, Sheila Heti, and Robin Wasserman have written remarkable novels about female friendship, but no one has tackled the complex search for female personal identity, and the construction of a feminine self through lifelong friendship, that is at the core of Elena Ferrante’s project in the quartet of works known as the Neapolitan novels: My Brilliant Friend (2011), The Story of a New Name (2012), Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay (2013), and The Story of the Lost Child (2015).

The ferocity of Ferrante’s writing style is what strikes most readers first. Her language is muscular, never orotund. It feels spoken, almost confessional. There appears to be no mitigation between her consciousness and the words on the page. In a 2015 interview in the Paris Review she said that sincerity is “the engine of every literary project.” She went on to say that she strives for literary truth in her writing, which she defines as “entirely a matter of wording” and “directly proportional to the energy that one is able to impress on the sentence.” This is a skill Ferrante says she has acquired over the years.

Not everyone agrees. Writing in The New York Review of Books, Tim Parks, the writer, critic, and translator of many leading Italian authors (Alberto Moravia, Antonio Tabucchi, Italo Calvino) claimed he can’t read more than 50 pages of Ferrante’s writing and finds it “wearisomely concocted, determinedly melodramatic.” He cites the scene of a fight between two neighbors. The women grapple with each other and roll down the stairs “entwined.” One of their heads hits the floor of the landing — “a few inches from my shoes,” reports Elena, “like a white melon that has slipped from your hand.” Parks comments: “As in a B movie, a head hits the floor a few inches from our hero’s shoes. Then comes the half-hearted attempt to transform cartoon reportage into literature: ‘like a white melon that has slipped from your hand.’” He finds Ferrante makes “no effort of the imagination,” simply “announces melodrama.” Indeed, he is “astonished that other people are not irritated by this lazy writing.”

James Wood has suggested that Ferrante’s writing is influenced by second-wave feminist writers such as Margaret Drabble and Hélène Cixous, and Ferrante has acknowledged her familiarity with the work of Cixous, Luce Irigaray, and Julia Kristeva. In a 2015 interview, when asked what fiction or nonfiction has most affected her, Ferrante also names Donna J. Haraway and “an old book” by Adriana Cavarero, Relating Narratives: Storytelling and Selfhood (1997). This is a useful clue. In her book, Cavarero directly addresses the subject of female identity. She posits that identity is not an innate quality we master and express, but rather the outcome of a relational practice, something given to us from another, in the form of a narratable “life-story.”

Cavarero first makes this point in “The Paradox of Ulysses,” using the scene from the Odyssey in which Ulysses listens to a blind rhapsode recount his exploits in the Trojan war and weeps, because for the first time he has become aware of the meaning of the story of which he is the hero. She then provides a “lived” example: the story of Amalia and Emilia, two women who meet at an adult education class devoted to raising the consciousness of women. [1] Emilia talks about herself constantly, telling Amalia that she has lived a repressed life. Yet she cannot shape a coherent narrative: “she wasn’t able to connect any of it up.” Amelia helps her by writing the story of her life based on what she has heard. “Once I wrote the story of her life […] she always carried it in her handbag and read it again and again,” and, like Ulysses, she was “overcome by emotion.” The story of Emilia’s life set down in writing by Amelia made her recognize that “my ‘I’ exists.” She needed this ontological affirmation of herself.

Cavarero’s conception of the formation of the feminine “I” factors directly into Ferrante’s writing. In a 2016 interview, Ferrante explained that “the female ‘I’ in particular, with its long history of oppression and repression, tends to shatter as it’s tossed around, and to reappear and shatter again, always in an unpredictable way.” Most of her female characters do, in fact, harbor an “other” violent “I,” one that emerges from anger, resentment, or a deep psychological wound. In The Days of Abandonment (2002), a pre-Neapolitan novel, the narrator, Olga, “accidently” feeds her husband pasta with crushed glass in it after he tells her he is leaving her; later, she physically attacks him in the street when she sees him with his new lover. In The Lost Daughter (2006), the violence is more subtle. Leda, a divorced mother of two, is vacationing at the beach. She befriends a mother, Nina, and her young daughter Elena. One day, spontaneously, Leda steals the little girl’s doll. [2] She tells us she took the doll because it “guarded the love of Nina and Elena, their bond, their reciprocal passion. She was the shining testimony of perfect motherhood.” While Nina and her daughter endure no end of pain and suffering because of the doll’s disappearance, Leda hides the doll in her apartment. It becomes a talisman, bringing back memories of her unhappy married life and the pain she caused her daughters by abandoning them and her husband for another man. The theft of the doll is a symbolic reenactment of shattering the “perfect motherhood.” And the violence she inflicts on the mother and daughter, seeing them suffer as she suffered, yields a perverse pleasure that assuages her wounded psyche.

¤

Of all Ferrante’s female protagonists, the narrator of the Neapolitan novels, Elena Greco, is the least interesting. Nevertheless, she is the direct descendent of the women Ferrante has been writing about for decades: they are all divorced or separated, vaguely middle aged, educated, industrious; for the most part they have risen above the poverty of their youth, but have had to fight for the nominal bourgeois social station they now inhabit. They are no strangers to rage, resentment, and existential angst, and they all attempt to discover themselves, to become who they are, or who they continually hope to be.

In The Days of Abandonment, Olga is abandoned by her husband and graphically chronicles her descent into a temporary psychotic state after his departure. As she struggles to remain “healthy” while surviving the dissolution of her married identity she ponders what will become of her. “What was I?” she wonders, and tells us: “This was the reality that I was about to discover, behind the appearance of so many years. I was already no longer I, I was someone else.” And this someone else wanted “to be me.”

We find this same struggle to recognize oneself in The Lost Daughter. Its narrator, Leda, tells us: “I had a sense of dissolving, as if I, an orderly pile of dust, had been blown about by the wind all day and now was suspended in the air without a shape.” While Elena is shrewder and more calculating than Ferrante’s previous heroines, her desires are more banal — “I want to get a driver’s license, I want to travel, I want to have a telephone, a television, I’ve never had anything” — and directed solely toward attaining success and the bourgeois lifestyle that accompanies it. But, while she wants these things, she keeps her wants suppressed and hidden from those around her, and asks herself if this is because she is “frightened by the violence with which, in fact, in [her] innermost self, [she] wanted things, people, praise, triumphs.”

In Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay, after she is published and married and successful, a reflective Elena informs us she has always been fascinated by the word “become”: “Become. It was a verb that had always obsessed me […] I wanted to become, even though I had never known what. And I had become, that was certain, but without an object, without a real passion, without a determined ambition.”

At one point, Elena’s mother-in-law gives her some books on Italian feminism by Carla Lonzi, one of the founders of the Rivolta Femminile, an Italian feminist collective. Elena says she knows well enough what it means to be a woman, and puts them away. But one day she picks up Lonzi’s seminal manifesto, “Let’s Spit on Hegel,” and it leaves her agape: “How,” she wonders “is it possible […] that a woman knows how to think like that. I worked so hard on books, but I endured them, I never actually used them, I never turned them against themselves. This is thinking. This is thinking against. I — after so much exertion — don’t know how to think.” Weary of her marriage, of domestic banality, Elena is suffocated by the life she chose. She tries to imagine what another life could be, wonders how she can create her “I,” but her imagination fails her. She is jealous of her sister-in-law who is single, attends political meetings, and is active in feminist causes.

Elena’s life careens from one thing to another; it is always “complicated” and hurried. She develops an “eagerness for violation” and chooses to engage suitors: “I was attracted by any man who gave me the slightest encouragement. Tall, short, thin, fat, ugly, handsome, old, married or a bachelor, if the [man] praised an observation of mine […] my availability communicated itself.” But, despite her education and exposure to “literary” texts, her desire to “become” someone doesn’t lead her to seek the causes of her taedium vitae, or to transform herself and transcend her current situation: it leads only to a man other than her husband. Once again, Ferrante references Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, whose heroine experiences a similar restlessness after marriage. No sooner is Emma Bovary ensconced in her country house with her husband than she finds herself unhappy — burdened with household chores and so disappointed in marriage that she begins to wish she was back in the convent in which she was raised. She dreams of escaping her fate. “But how,” Emma wonders, “to speak about so elusive a malaise, one that keeps changing its shape like the clouds and its direction like the winds?”

This modern-day malady from which Emma and Elena suffer, “malaise,” is related to ennui — what we prosaically refer to as boredom. It is the “noonday demon” of the ancient Christian fathers, and Baudelaire’s “delicate monster.” What Flaubert’s and Ferrante’s characters are trying to articulate is a presentiment that the eternal return of days — days filled with chores and the petty needs of others — can’t be all there is. What nags at them is the feeling that strikes us all when, in a funk, we ask ourselves: Is this really my life? Is this all there is? What would “more” be?

Elena’s own malaise remains similarly unnamable. Ferrante allows Elena to bemoan her unhappy life for well over a thousand pages, to wallow in the “cycle of ennui,” from which there may sometimes be no escape except the one offered by Flaubert. Of course, Elena doesn’t meet a tragic end. Ferrante does finally allow her to free herself (at least temporarily) from her lifelong predicament and shows us, briefly, what living without “the monster” would be like. This demonstration takes place late in the last volume of the tetralogy, at which point Elena has gained literary recognition, abandoned her husband and her children, and has been living with her lover, Nino, for a year and a half: “It was then that — we said to each other — our true life had begun. And what we called true life was that impression of miraculous splendor that never abandoned us even when everyday horrors took the stage. […] We hurried to dinner, to good food, wine, sex.” So “true life” appears to be nothing more than the commonplaces of bourgeois material success. Elena includes Nino in her declaration, but he doesn’t seem to have bought into this view. While she is waxing exuberant about the “true life” they are leading, he is busy having sex with the nanny. Soon, the couple separates. As Elena discovers, her notion of “true life” is just as misguided as Emma’s belief that “certain portions of the earth must produce happiness — as though it were a plant native only to those soils and doomed to languish elsewhere.”

What is deeply disappointing about Elena is her inability to transform herself — even though she seemingly has the intellectual capacity for it. We feel that if she had perhaps dedicated herself more to intellectual and spiritual matters instead of “cultivating resentment” she might have progressed toward some sort of enlightenment. At times, we feel the tension between her lucid self-awareness and latent self-actualization. Ferrante keeps us teetering with anticipation of change as we read page after page of Elena’s ruthless psychological insights, and witness her pathological excavation of her feelings. We keep hoping for a catharsis that never comes. One could argue, with reference to Adorno, that the “jargon of authenticity” she employs in search of her ever-elusive “I” is nothing more than narcissism.

The truly interesting character in the Neapolitan novels is Lila. She is a marvel. Unconventional, volatile, aggressive, ambitious, by turns emotionally stingy and generous, she is both intellectually gifted and entrepreneurial. She is self-possessed and unpossessable. By the time she is an adolescent, it is apparent to Elena that Lila “took the facts and in a natural way charged them with tension; she intensified reality as she reduced it to words, she injected it with energy.” While Elena worries about her appearance and her attractiveness to boys, Lila has already apprehended how the world works. From an early age, she is keenly aware of both the social and political injustices people of her impoverished class (whom the cruel, bitter teacher Maestra Oliviero refers to as “plebs”) are forced to suffer; and she also grasps, with Roquentin-like perspicacity, the meaninglessness of existence.

At 15, just before Lila is married, Elena, proud of her book learning, attempts to impress her friend with her knowledge of theology. Lila responds tartly: “You still waste time with those things? […] There are microbes everywhere that make us sick and die. There are wars. There is a poverty that makes us all cruel. Every second something might happen that will cause you such suffering that you’ll never have enough tears.” Throughout her childhood and youth, Lila takes more beatings than MMA champion Ronda Rousey. Her father throws her out the window and breaks her arm. Her brother pummels her over a disagreement about the shoes they are designing. “Every time Lila and I met,” says Elena, “I saw a new bruise.” Her boyfriend, and later husband, Stefano, beats her relentlessly, sometimes even punching her in the face. He rapes her on their honeymoon, from which she returns black and blue, and her married life is characterized by systematic abuse. Elena is continually amazed at her friend’s capacity for suffering, but Lila explains: “What can beatings do to me? A little time goes by and I’m better than before.”

Lila is “capable of anything.” Within the first year of her marriage, she embarks on a reckless affair with the love of Elena’s life, Nino. She then leaves her husband, an act unheard of in those days, to move in with him. As Nino says, “[S]he doesn’t know how to submit to reality […] and takes no account of police, the law, the state.” When they break up she takes another lover, with whom she founds a business and makes a success of herself. When, in The Story of a New Name, the Mafioso Michele Solara and his brother want to use her photograph to sell shoes that she has designed, Lila defaces the picture; using glue, scissors, paper, paint, she “erases” herself, refusing to allow others to use her image, refusing to be appropriated for any purpose. In the final volume, The Story of the Lost Child, even after having had great success in the computer business, she tells Elena, “I want to leave nothing, my favorite key is the one that deletes.”

Like Elena, Lila writes. Over the years, she amasses volumes of notebooks of her thoughts and observations, and in The Story of a New Name she gives them to Elena to keep her husband from finding them. Lila makes Elena promise she won’t read them. Naturally, Elena devours the texts. She is overwhelmed and “diminished” by them. She devotes herself to learning passages by heart — “the ones that thrilled me, the ones that hypnotized me, the ones that humiliated me. Behind their naturalness was surely some artifice, but I couldn’t discover what it was.” Eventually, she throws the notebooks off the Solferino bridge into the River Arno, in order to free herself from feeling Lila “on me and in me.” But she can’t erase Lila from herself.

Late in life Lila begins another writing project, one she will not share with Elena, which once again makes Elena feel inadequate. When Elena then suggests she may write about Lila, Lila says, “Let me be.” She tells Elena to write about someone else, “But about me no, don’t you dare, promise.” Lila wants nothing more than to disappear, while Elena “wanted her to last […] I wanted it to be I who made her last.” She wants to write her life-story.

Against Lila’s wishes Elena writes and publishes a book about the two of them, which she titles A Friendship. It is — implausibly — only 80 pages long. The book is a success and revives Elena’s sagging career, but after its publication, the two women never speak again and Lila disappears. Thus, contrary to Cavarero’s contention, which invokes Ulysses listening to his own life-story, Lila doesn’t need a life-story written about her in order to affirm her “I.” If another were to write her life-story, she would be turned into “fiction,” taken possession of. And just as she never let anyone possess her throughout her life, she has no intention of allowing that to happen once she is gone. She won’t participate in a practice that reduces her ontological presence to words on a page, a fetishized object between covers. By vanishing, she asserts her right to live a “mere empirical existence.” It is a brilliant move on Ferrante’s part to allow her subject to refuse subjugation to the art of “story telling,” even as she (and Elena) tell her story in the very book we are reading.

Long before the end of the novel, Elena goes to visit Lila, who is at her nadir, a proletariat slaving away at a sausage factory right out of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. Elena has come to brag about her success as a writer: “I had made that whole journey mainly to show [Lila] what she had lost and what I had won.” Instead, she finds Lila

explaining to me that I had won nothing, that in the world there is nothing to win, that her life was full of varied and foolish adventures as much as mine, and that time simply slipped away without any meaning, and it was good just to see each other every so often to hear the mad sound of the brain of one echo in the mad sound of the brain of the other.

And indeed, Ferrante’s searching Elena and elusive Lila will continue to echo each other, and to resonate for readers, in all their irreducible complexity.

¤

GD Dess is the author of the novel Harold Hardscrabble.

¤

[1] The story of Amalia and Emilia recounted by Cavarero first appeared in Sexual Difference: A Theory of Social-Symbolic Practice, one of the most famous books of Italian feminism. Sexual Difference may also have influenced Ferrante’s thinking about the friendship between Elena and Lila, the two main characters in the Neapolitan novels. The social practice of “entrustment,” the idea that one woman “entrusts” herself symbolically to another woman is one of the major ideas of Italian feminism. In My Brilliant Friend, Elena tells us of her decision to reject her mother as a model and give herself over to Lila: “I decided that I had to model myself on that girl, never let her out of my sight.” This practice is viewed as necessary “because of the irrepressible need to find a faithful mediation between oneself and the world: someone similar to oneself who acts as a mirror and a term of comparison, an interpreter, a defender and judge in the negotiations between oneself and the world.”

[2] Children are regularly treated brusquely, beaten, and/or suffer from benign, and not-so-benign, neglect in Ferrante’s novels. In the essay “What an Ugly Child She Is,” Ferrante responds to a Swedish publisher’s refusal to publish The Days of Abandonment because of the “morally reprehensible” way in which the protagonist treats her children. In that novel, Olga is chiefly guilty of neglect and indifference, abruptness and aloofness in her treatment of them; she does not harm them physically, although she is a bit rough in removing the makeup from her daughter who has, to her disgust, made herself up to look like her.

In defense of her portrayal of Olga’s behavior, Ferrante references Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, and the scene in which Emma Bovary, upon being pestered for attention by her young daughter, Berthe, angrily shoves the girl with her elbow, causing the child to fall against a chest of drawers and cut herself. The wound begins to bleed. She lies to the maid, telling her: “The baby fell down and hurt herself playing.” The wound is superficial. Emma stops worrying about what she had done, forgives herself for her abusive behavior, and chides herself for being “upset over so small a matter.” And then, still sitting by her daughter’s side as she recuperates, adding insult to injury, she thinks: “It’s a strange thing […] what an ugly child she is.”

Ferrante comments that only a man could write such a sentence. She claims (“angrily, bitterly”) that men “are able to have their female characters say what women truly think and say and live but do not dare write.” She says her attempt has been, “over the years, to take that sentence out of French and place it somewhere on a page of my own.”

She does create a scene similar to Flaubert’s in The Lost Daughter. Leda, the narrator, tells us that when her daughter was young, she gave her a doll that had belonged to her since infancy. Leda expected her daughter to love the doll. But her daughter strips the doll of her clothes and scribbles over her with markers. When Leda discovers her sitting on the doll one afternoon, she loses her temper, “gives her a nasty shove,” and throws the doll over the balcony. It is run over and destroyed by the passing traffic. Leda’s only (ominous) comment about this incident: “How many things are done and said to children behind the closed doors of houses.”

10 BOOKS ON ECSTATICALLY MAD WOMEN

JESSIE CHAFFEE READS DEEPLY INTO EMPTINESS, FEAR, DESIRE, AND ELATION

July 3, 2017 By Jessie Chaffee

When I was 22, I developed an eating disorder, an experience equal parts horror and euphoria that took me outside of myself, turning me into someone I wasn’t, or perhaps revealing a part of me that had always been there. Intellectually, I recognized that I was negating, erasing, and isolating myself. But my emotional experience was not one of loneliness or loss. On the contrary, I often felt painfully clear, high, satiated, connected to something more than myself. I felt ecstatic.

By the time I sought help, I was whittled down, haunted, and searching for a way to describe those months when I had disappeared from my life. I had always identified as a writer, but anorexia stripped me of words, alienating me from the world as I previously understood it and from the language I used to give shape to that world. In its wake, I was searching for a new language, one that, as a lifelong reader, I hadn’t yet witnessed in literature.

And then a close friend handed me a copy of Jean Rhys’s Good Morning, Midnight. Like many people, I had read Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea, a retelling of Jane Eyre from the perspective of Bertha (aka, “the madwoman in the attic”), but this novel, published decades earlier, was different. It was unlike anything I’d ever read in its depiction of a woman who is losing herself to the seduction of alcoholism, the ghosts of her past, and the increasingly self-destructive decisions she makes as she tries to survive both. What was new was not the content but the telling. Rhys collapses the distance between the reader and her protagonist. We don’t witness Sasha’s descent; we live it. We feel the too-small dirty hotel room, the jeers and stares of strangers who may or may not actually be there, the grief and weight of memory. And we feel the messy intermingling of emptiness, fear, desire, and elation as reality unravels, and language with it, along the beautiful and horrific knife-edge of addiction.

Good Morning, Midnight gave me not only a mirror for my own experience, but it altered completely the type of work I wanted to produce as a writer. I consumed the slim, used paperback in a single sitting—and consumed is the right word, as it nourished me, became a part of me, and then left me hungry for more writing like it. From Rhys, it was not a far leap to Marguerite Duras and then Elena Ferrante and Claire Messud, all women who write about women on the fringes grappling with the most foundational questions of meaning and identity. These writers deal in contradictions, in the seductive gray areas where the high lives, in the things that might destroy us but that we nevertheless pursue. Their protagonists are complicated, flawed, brilliant, extreme, and, quite often, ecstatic.

I began writing my novel out of a desire to be in conversation with those writers, and to give language, through fiction, to an experience that had left me mute. In the writing I realized that there was another group of women writers whose stories I needed to read—the Catholic mystical saints, women who claimed a direct relationship to God through their ecstatic visions, and who recorded those visions in fiery and sensual language. Their vitae read like the ancestors of Rhys and Ferrante. Their ecstasies were not always celebrated—they were also used as evidence that they were possessed, deceitful, or calculating in their ambition. But like the protagonists of their contemporary counterparts, the saints’ telling leaves no room for doubts as we live the experiences with them.

Below are my favorite works about ecstatic women brought to life by my favorite women writers. These narratives don’t grant us the safety of distance or room for judgment, but place us within the protagonists’ realities, daring us to feel what they feel, and suggesting that if ecstasy is madness, then we the readers are mad too.

Elena Ferrante, The Days of Abandonment, tr. Ann Goldstein

Written before the uber-popular Neopolitan novels, this slim, visceral work follows a woman’s violent struggle to make meaning in the chaos and isolation that follows the dissolution of her marriage:

I was not the woman who breaks into pieces under the blows of abandonment and absence, who goes mad, who dies. Only a few fragments had splintered off, for the rest I was well. I was whole and whole I would remain. To those who hurt me, I react giving back in kind. I am the queen of spades, I am the wasp that stings, I am the dark serpent. I am the invulnerable animal who passes through the fire and is not burned.

Likely Stories: The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante

By JIM MCKEOWN • FEB 9, 2017

Intense adult story of a woman suddenly and inexplicably abandoned by her husband.

I’m Jim McKeown, welcome to Likely Stories, a weekly review of fiction, non-fiction, poetry, and biographies.

I have been a fan of women’s literature for many years. One such author has eluded me until a recent article discussed the Italian writer, Elena Ferrante. My first actual encounter with Ferrante’s works occurred after a trip to the marvelous independent bookstore, Inkwood Books of Haddonfield, N.J. I asked the clerk about Ferrante, and she suggested the “Neopolitan Quartet” of novels, which was sold out, but she did have a copy of the Days of Abandonment. Across the street from the shop was a coffee bistro, so I went for a coffee and a scan of the novel. About an hour later, I was hooked, and I accepted the fact this was a powerful novel by a writer I could not let slip by me.

Days of Abandonment tells the story of a woman abandoned by her husband, Mario, who takes up with a young woman, Carla, half his wife’s age. The novel begins, “One April afternoon, right after lunch, my husband announced that he wanted to leave me. He did it while we were clearing the table; the children were quarrelling as usual in the next room, the dog was dreaming, growling beside the radiator. He told me that he was confused, that he was having terrible moments of weariness, of dissatisfaction, perhaps of cowardice. He talked for a long time about our fifteen years of marriage, about the children, and admitted that he had nothing to reproach us with, neither them nor me. He was composed, as always, apart from an extravagant gesture of his right hand when he explained to me, with a childish frown, that soft voices, a sort of whispering, were urging him elsewhere. Then he assumed the blame for everything that was happening and closed the front door carefully behind him, leaving me turned to stone beside the sink” This is the tiniest of sparks which will turn into a conflagration of immense power.

Readers, I want to make you aware this is an adult novel based on a single chapter when Olga vents all her rage, jealousy, and fury, in a scene of a rather explicit and volcanic nature. A reader will know when it starts, so it is easy to skip. This novel is the most incisive and detailed account of the agony a woman undergoes when she is abandoned by her partner. The prose is mesmerizing and gripping. I could barely put it down for a moment. Here is a scene when Olga decides to seek revenge on her husband with a man from her building she despises. [Carrano] “again brought his lips to mine, but I didn’t like the odor of his saliva. I don’t even know if it really was unpleasant, only it seemed to me different from Mario’s. He tried to put his tongue in my mouth, I opened my lips a little, touched his tongue with mine. It was slightly rough, alive, it felt animal, an enormous tongue such as I had seen, disgusted, at the butcher, there was nothing seductively human about it. Did Carla have my tastes, my odors? Or had mine always been repellant to Mario, as now Carrano’s seemed, and only in her, after years, had [Mario] found the essences right for him” (80-81). You can now skip to page 88. Not for the faint of heart, this novel is a masterpiece of the inner workings of the mind of a woman. 5 stars.

FROM THE DESK OF MATT POND PA: ELENA FERRANTE’S “THE DAYS OF ABANDONMENT”

I’m looking up at a coffee shop full of strangers, and I can’t help but think that we seldom welcome people as they are anymore—including me. The curation of our profile and personhood is just about the slipperiest slope out there.

The Days Of Abandonment. There are some reviews that consider the descent of main character to be clichéd. After a lifetime of familial dedication, Olga is abandoned by her husband Mario. She goes down, disrupted and scouring the depths of sanity.

While the signposts may be similar to those that have already appeared, the description and intensity of the Olga’s dive are incomparable. It’s a palpable pain that brings me closer to a grief-case I’ve grown accustomed to hiding from everyone, including myself.

Both disturbing and real—from here on out, I’m on a treasure hunt for everything that matters. A quiet quest for all that beguiling dirt beneath our shuffling feet.