Guest Post: A New Consideration of Elena Ferrante’s The Beach at Night by Dr. Ellen Handler Spitz

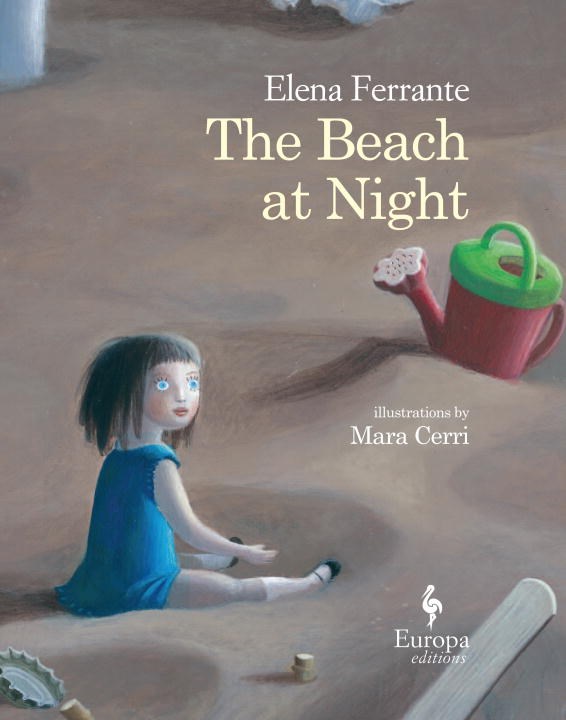

You guys know my penchant for children’s books that fall outside the usual norms. And nothing strikes fear in the good American heart faster than picture books from other countries. I’ve seen even the most sophisticated of readers wrinkle their noses at translations they deemed “weird”. And nothing caused such wrinkling better than the 2016 publication of the American edition of Elena Ferrante’s picture book The Beach at Night. Kirkus argued that the book was not, “a true picture book: with many text-only double-page spreads and illustrations that do little to extend the text, this book will try the patience of most young listeners. The Italian edition of this book is marketed to children 10 and up; the advertised audience in the United States of 6 to 10 feels just plain wrong.” The New York Times was hardly any more kind. And yet, it has its defenders.

Today, guest poster Dr. Ellen Handler Spitz, author of such books as The Brightening Glance: Imagination and Childhood and many others, comments on the book and its reception. Take it away, Ellen!

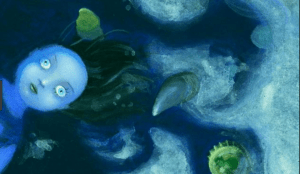

Mysterious, hugely popular Italian novelist Elena Ferrante wrote a children’s book, The Beach at Night, that has curried scant favor in the American press since its 2016 translation by Ann Goldstein. I would like to advocate, albeit gently, for this book. A doll named Celina, left behind on a beach at the end of one day by five-year-old Mati, tells us how that feels: the story is told in her voice, that of an anthropomorphic toy.

Mysterious, hugely popular Italian novelist Elena Ferrante wrote a children’s book, The Beach at Night, that has curried scant favor in the American press since its 2016 translation by Ann Goldstein. I would like to advocate, albeit gently, for this book. A doll named Celina, left behind on a beach at the end of one day by five-year-old Mati, tells us how that feels: the story is told in her voice, that of an anthropomorphic toy.

Ferrante’s theme— abandonment —touches children’s deepest fears. It plays out within the intimate, oft blurry bonds between a little girl, her doll, and her mother. With short, direct sentences, Ferrante unfurls a catalogue of woe. Being neglected comes first, as Celina watches Mati go to play with Minù, the new kitten her visiting father has just brought her. Humiliation arrives next. Rejected and cast off on the beach, Celina suffers maltreatment by Mati’s grumpy brother, who dumps burning sand on her. Physical discomfort follows fast, and then terror, as the family leaves the beach without her, and the sky changes color. A “Mean Beach Attendant” with a huge Rake frightens her and flings her onto a pile of trash. Fear morphs into sadness and anger. Anxious about being hurt and broken, Celina remembers Mati’s former love. Envy comes barreling in, as she pictures the kitten Minù who has supplanted her and wants spitefully to spoil him. Vindictively, she conjures him having bouts of diarrhea and imagines vomiting on him so that Mati will be compelled to forsake him: an apt projection on Ferrante’s part, since little girls, when expected by their mothers to be clean, may feel unlovable when not.

Loneliness and boredom ensue. Followed by confusion. The Mean Attendant ignites a fire to burn residual beach trash, including Celina. She uncomprehendingly welcomes its warmth because the sunless beach has grown cold. Gradually, however, she understands that the fire which pleases her can destroy her. When it scalds her dress, she chides (as to a naughty pet): “Bad fire.”

Ferrante is partaking, of course, in a time-honored tradition in which dolls come to life in children’s books. Two long-lived examples might be cited: Rachel Field’s Newbery Award-winning Hitty of 1929, in which a doll carved from magical wood recounts her hundred year journey, and the ever-beloved Raggedy Ann stories of c. 1900, in which a stuffed rag doll with a candy heart from grandma’s attic has nocturnal escapades that author Johnny Gruelle based on observations of his daughter Marcella. Turning to animation, there’s Pixar’s Toy Story of 1995, by John Lasseter. Ferrante mines this vein in several novels, including The Lost Daughter and My Beautiful Friend, where dolls play quasi-human roles. Her pages, however, often portray toy characters in nightmarish settings fraught with anxiety.

The Beach at Night, moreover, employs language unpurged of slang (for which, however, as New York Times reviewer Maria Russo points out, the translator may be held responsible), and, as I have emphasized in Inside Picture Books, a reading adult is always free to substitute one word for another. The term “caca,” translated here with an expletive, might easily be rendered by the childish expression “doo-doo.” Nevertheless, Ferrante’s book has been judged by some to be inappropriate for children. Respectfully, I demur.

Many books for young children tend to be protective; only rare ones plumb the intensity of feeling to which small children are prey. Maurice Sendak’s oeuvre, of course, stands as an exception. As does Ferrante’s The Beach at Night. Like Jezibaba or Medea, Ferrante dips into the cauldron without gloves, seizes fears, yanks them out, and thrusts them under the glaring strobe lights of her prose. In so doing, she performs a service not unlike that of Sendak, who, in his masterpiece Where the Wild Things Are, unfastens a door and shoves us in, or, better yet, pushes us in and closes the door fast behind us.

Many books for young children tend to be protective; only rare ones plumb the intensity of feeling to which small children are prey. Maurice Sendak’s oeuvre, of course, stands as an exception. As does Ferrante’s The Beach at Night. Like Jezibaba or Medea, Ferrante dips into the cauldron without gloves, seizes fears, yanks them out, and thrusts them under the glaring strobe lights of her prose. In so doing, she performs a service not unlike that of Sendak, who, in his masterpiece Where the Wild Things Are, unfastens a door and shoves us in, or, better yet, pushes us in and closes the door fast behind us.

Perhaps you are wondering: But, why explore pain in a children’s book? My best reply would entail a wondrously wise 1959 text called The Magic Years by Selma Fraiberg, distinguished University of Michigan psychologist. This classic exploration of young children’s inner lives unsurpassed for more than a half-century tells a cautionary tale about Frankie, a little boy whose devoted parents are eager to do him right. They consult experts, identify typical childhood fears, then systematically keep those fears at bay. Nursery rhymes are edited; fairy tales purged of witches and ogres. When a pet parakeet dies during Frankie’s nap, it is replaced before he can notice. His baby sister’s birth is planned to minimize feelings of jealousy, rivalry, and displacement. Yet, Frankie suffers all the ordinary fears of early childhood and bad dreams as well. Endemic to human growth, Fraiberg explains, fears emanate largely from within. Since they cannot be expunged, growing children need to learn to invent solutions, as Fraiberg puts it, “to the ogre problem.” Ferrante’s Mean Beach Attendant, for example, replete with lizard-like moustaches and nasty ditties seems merely an update of the ogre or bogeyman, familiar from European folk tales.

Elena Ferrante gets this. Her fierce grasp of its truth informs her slender book. No emotion in The Beach at Night is foreign to young children because, as we have come to recognize, at least since the late 19th century, even the youngest have active inner lives despite their lack of words with which to report on it. Fear, envy, confusion, longing, disappointment, anger, and sadness are all poignantly felt. That said, where better to practice coping than in the pages of a story book? Children who encounter danger in books, especially with adults present to help interpret, can do so safely. If intense emotional exploration serves a boon in art and literature for grown-ups, why should it not be made available for children? The Beach at Night offers vicarious adventures that, for some children, may provide a proving ground for mastery, while for others, undeniably, its scenes will be too scary. Parent-and-child or teacher- or librarian-and-child may collaborate to make that call, and this in itself can constitute valuable learning.

Abandonment tops the list of childhood terrors. A college student of mine surprised me in class when she nailed the most abject horror of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Match Girl. Not darkness, she whispered. Not freezing cold. Not starvation. But the fact that the little girl cannot go home. Cast out, she dies on an empty city street.

Ferrante plots Celina’s abandonment with exquisite care. Good turns suddenly to evil and then occasionally reverses. Mati’s love for her doll Celina morphs into rejection. The hot beach becomes chilly at night. The comforting fire harms what it warms. A sea wave saves Celina from fire but then engulfs and nearly drowns her. The aptly colored black and white kitten starts as a rival for Mati’s affection but ends up being the creature who improbably saves her, brings her home, and becomes, at the book’s end, her friend. Mati’s father, kindly giver of the kitten, serves as a foil for the other adult male character, the Mean Beach Attendant, who calls Celina “ugly” and nearly annihilates her.

Ferrante plots Celina’s abandonment with exquisite care. Good turns suddenly to evil and then occasionally reverses. Mati’s love for her doll Celina morphs into rejection. The hot beach becomes chilly at night. The comforting fire harms what it warms. A sea wave saves Celina from fire but then engulfs and nearly drowns her. The aptly colored black and white kitten starts as a rival for Mati’s affection but ends up being the creature who improbably saves her, brings her home, and becomes, at the book’s end, her friend. Mati’s father, kindly giver of the kitten, serves as a foil for the other adult male character, the Mean Beach Attendant, who calls Celina “ugly” and nearly annihilates her.

All these turnabouts match young children’s mental lives, where perceptions reverse in a flash. The hand that caresses stiffens into a spank. The angry grimace softens to a twinkle. Lacking analytical ability as yet and information with which to explain these turnabouts, children find their unpredictability both magical and terrifying.

Darkness matters. Night is when mysterious events take place. And Ferrante uses the beach elsewhere in her work, especially in The Lost Daughter, where her protagonist “rescues” a doll forgotten on a beach and then holds on to it, unable to bring herself to return it to the child who longs for it. As in The Beach at Night, which it eerily overlaps, The Lost Daughter blurs boundaries between girl and doll, mother and daughter, boundaries breeched again by Ferrante in the opening pages of another novel My Brilliant Friend, were two girls play in tandem with their dolls, conversing with them and imitating each other like miniature characters in a Pirandello play until the one with the ugly doll throws another’s beautiful toy into a dark cellar.

A paradigmatic moment in The Lost Daughter occurs when the narrator, mother of two faraway grown daughters, anxiously watches a young mother on the beach with her little girl and a doll. Eavesdropping, she hears the names of mother, daughter, and doll all seem to mingle and merge: Nina, Ninù, Niné, Nani, Nena, Nennella, Elena, Leni. Switching back and forth from childish to grown-up voices as they play, this mother and daughter make the mute doll “speak” as if it were both mother and child without separation. Envious of their fluidity and yearning for lost moments in her own life, the narrator finds the scene intolerable. Unhinged, she rises to intervene, willing them to stop.

That Lost Daughter scene illuminates a key moment of recognition in The Beach at Night. The beach has turned dark; no stars or moon appear, and the abandoned doll Celina recalls her little mistress Mati saying to her in her mother’s voice, “If you catch cold, you’ll get a fever.” Suddenly, the doll understands: Mati is repeating her own mother’s words “because Mati and I are also,” as Ferrante writes, “mother and daughter.” The next thought is surely what Aristotle would have called a peripeteia. Celina comprehends that, because of this identification, Mati cannot possibly have forgotten her. She is not abandoned! And children encountering the story understand. On the last page but one, Mati, having Celina back, hugs her with a face wet with tears.

What then is Celina, the doll? The renowned British pediatrician and psychoanalyst Donald W. Winnicott coined the term “transitional object.” He meant by this a blanket, stuffed animal, or dolly that is neither exclusively the child’s “me” (self) or “not-me” (other) but a quirky amalgam that gets created in the context of the closest human relationship and used to play it out. Ferrante shows us this small miracle and never lets up. Right there on the sand, each of us is led through the dread of abandonment. But, as we close the book with our children, we may feel more aware of and grateful for the loved ones who abide with us, both child and adult.